Until recently, I didn’t filter my family’s water. This meant the water we drank, cooked with, showered with, bathed in, and used to water indoor and outdoor plants contained a small amount (up to four parts per million) of chlorine.

Of course, I would have preferred to drink water without chlorine. In fact, I would have preferred to drink pristine water from a high-mountain spring. But I accepted drinking a small amount of chlorine as an imperfect necessity, similar to breathing in automobile pollutants outdoors. I grew up drinking unfiltered water and swimming in a chlorinated pool, so chlorine didn’t feel like a huge health threat. Moreover, the Environmental Protection Agency contends water chlorination is unlikely to cause harm to human health.

But one day as I was feeding my sourdough starter, I had a revelation. I’m careful to boil and cool tap water for my starter because chlorine is toxic to microflora. (That’s why it’s added to tap water after all.) So why would I subject the microbiome in my mouth and gut and on my skin to it?

Befriending Bacteria

We’re in the midst of an exciting scientific paradigm shift. Scientists mapped the genome of the human microbiome in 2012 and discovered we have trillions of microbes living with us. If that discovery makes you want to reach for an antimicrobial agent, don’t do it! It would be impossible to wipe out your microflora. And when we disrupt it, we risk harm to ourselves. Research indicates microbes are critical to our health in amazing and surprising ways. They’re integral to the functioning of the gastrointestinal and immune systems, they help the body metabolize environmental pollutants, and they produce vitamins B, B12, K, thiamin, and riboflavin, which coagulate the blood.

Numerous conditions are linked to dysbiosis (an imbalance in microbiota), including inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, autism, cancer, gum disease, depression, acne, and other skin disorders. We don’t know if dysbiosis causes these disorders. But it’s notable that many of these disorders were uncommon until the last century, when we started waging a war on germs.

It’s now widely understood that antibiotics should only be prescribed when absolutely necessary. (In one study, a week-long course of antibiotics changed participants’ gut microbiota for up to a year.) It’s acknowledged that the antimicrobial agent Triclosan does more harm than good. Researchers are raising questions about the antiseptic mouthwash chlorohexidine, which dentists prescribe for gum disease. It’s linked to increased blood pressure because it kills beneficial bacteria in the mouth that help the body regulate blood pressure. (Moreover, it’s implicated in the growth of antibiotic-resistant superbugs.)

But what about chlorinated water? How does it affect our microflora?

“It’s something I’ve discussed with a number of other microbiologists,” Jeff Leach, a leading microbiome researcher, told Josh Harkinson for an article in Mother Jones. “In short, nobody has done the research, but we are certain that there is an impact.”

Caring for the Ecosystems Within

The human microbiome consists of vast ecosystems of species. They’re not random collections of floating microbes. They’re organized and structured and function like forest ecosystems.

If you’ve studied wildlife management, you know human actions can have hugely negative impacts on an ecosystem. For example, when scientists remove predators in an ecosystem, they can unwittingly transform a biodiverse habitat into a monoculture. In a 1966 experiment, scientists removed the purple starfish from the Washington coast. The population of mussels (the purple starfish’s food source) exploded and crowded out algae and other plant life.

If you’re a gardener, you’re probably more familiar with what happens when you clear the plants in a garden and leave behind bare soil. Weeds are usually eager to invade.

So what happens when we potentially restructure our inner ecosystems every time we take a sip of water? Are we wiping out beneficial microbes that keep pathogens in check? Could this help to explain why up to 75 percent of Americans have some form of gum disease (compared to 5 percent of people found in an ancient burial site)? Could it help to explain why inflammatory bowel diseases are now epidemic? We don’t know, but I’d like to see more research on the topic.

Public Health Concern

According to the majority of public health experts, chlorinated water is a triumph that has saved lives and dramatically decreased cholera, typhoid fever, and other deadly illnesses. This may be so. However, public health interventions must be routinely assessed. We need to weigh negative and positive implications in light of new understandings about human health. This is particularity true in the case of chlorination, which researchers have linked to higher incidences of bladder, rectal, and breast cancers. Chlorine is not considered a carcinogen. However, trihalomethanes and other organic compounds, which are byproducts of chlorination, are carcinogens.

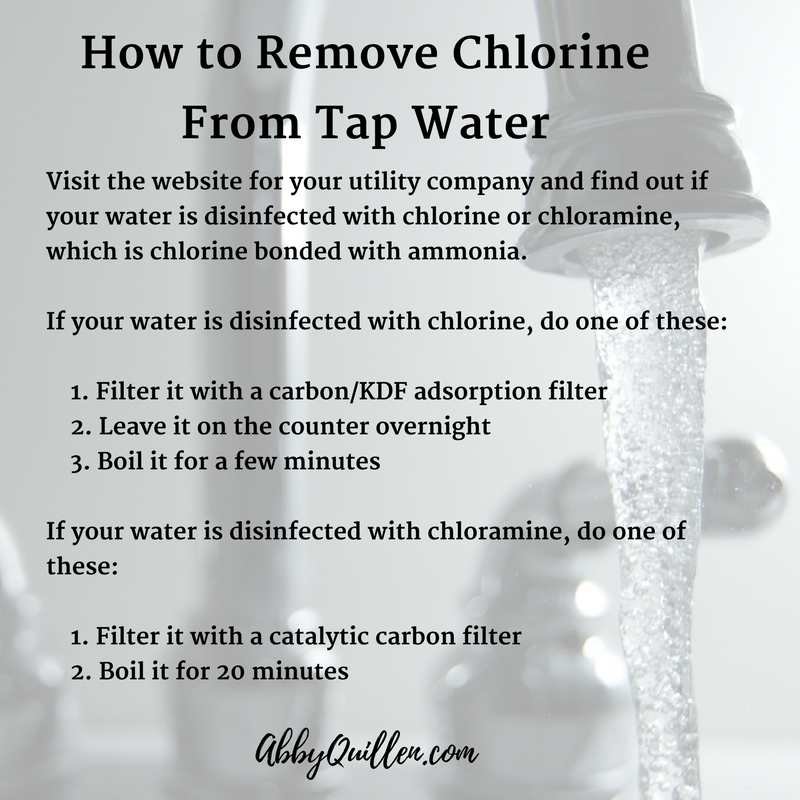

Water chlorination started in 1908, and there may now be better ways to keep our water supply safe today, such as ozonation (used in Las Vegas, Canada, and Europe), ultraviolet light, or treating water with beneficial bacteria. While we wait for more research and new technology, though, you’ll need to take measures to remove the chlorine in your water if you don’t desire to drink it.

Conclusion

We are on the frontier of understanding how the health of the microbiome impacts human health. As more research accumulates, public health measures, medical practices, and self-care recommendations are likely to change. For now, it’s up to us to weigh the research and decide how to care for our bodies and the microbes that share them.

Photo credit: Steve Johnson